‘Let’s howl, said the dog.’

Epigraph to Seeing (2004) by José Saramago

In the UK, there is a long tradition of rejecting all available alternatives in an election by spoiling one’s ballot paper. The French, inevitably, have a more elegant method. Reasoning that abstention can be attributed to apathy or idleness as well as disapproval, and that there is no way to distinguish ballots spoiled in error from those spoiled in protest, un vote blanc, in which the ballot is returned completely blank, stands in silent condemnation of all the candidates. In a recent hypothetical discussion of this Sunday’s second-round of the French presidential elections, the majority of my comrades declared that, faced with the impossible choice between Macron and Le Pen, they would cast un vote blanc. Despite the anti-fascist imperative of keeping Le Pen out of the Élysée Palace, it is hardly surprising that a group of socialists should have come, however reluctantly, to this conclusion. It is, after all, the apparent position of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the standard-bearer of the French left, who has been as steadfast in his refusal to endorse Macron as he has been emphatic in his prohibition of voting for Le Pen. Some polls predict that the majority of those who voted for Mélenchon in the first round, some 22% of the French electorate, will indeed either abstain or cast blank votes on Sunday. Withdrawing in disgust is not, of course, the same thing as apathy.

For what it’s worth, as much as I can sympathise with and respect such a decision, I cannot endorse it. For me, this refusal to vote is, perhaps paradoxically, symptomatic of an attitude that venerates and sanctifies the electoral process above all other forms of political engagement and activity. It is a curious type of idealist individualism that, in spite of all evidence to the contrary, conceives of voting as the pure expression of one’s beautiful political soul, and that to vote tactically or half-heartedly or with the proverbial clothes peg on your nose sullies the sacred process. It’s an attitude that is incompatible with any type of radical politics worthy of the name. Often — and Sunday’s French election seems to me just such a case — voting has to be understood less as an expression of personal choice than as a gesture of collective solidarity. If the examples of Brexit and Trump’s victory in 2016 are any precedents, then the first response to a Le Pen victory on Sunday will be a terrifying spike in hate crimes against minorities, especially France’s Muslims. As loathsome as Macron undoubtedly is, that fact alone would compel me to vote against Le Pen.

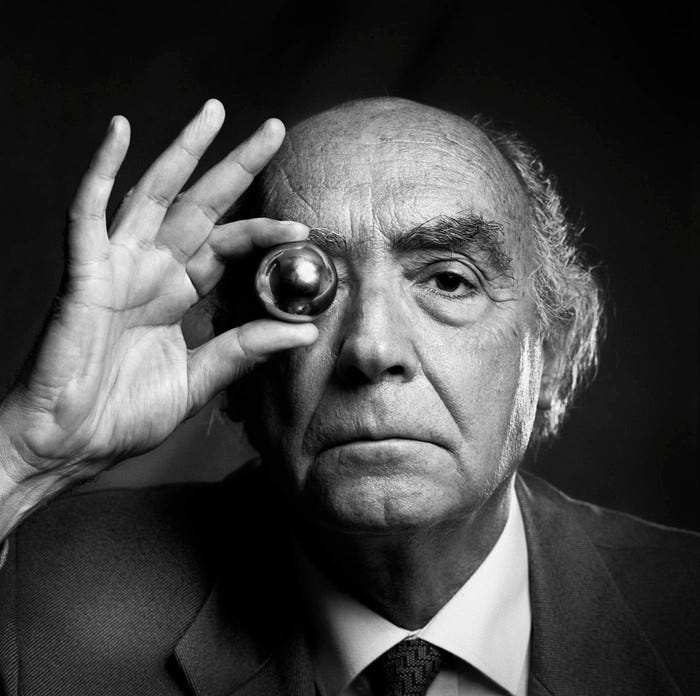

In any event, this discussion of votes blanc, has put me in mind of perhaps the greatest contemporary novel about politics that I know: Seeing (2004) by the Portuguese Nobel laureate José Saramago. Like all of Saramago’s novels, the deceptively simple, fable-like narrative belies a profound moral and political subtlety expressed in prose that can seem at once provocatively experimental and disarmingly direct. The message of this parable about a city that utterly derails the smooth running of the social order merely by casting mostly blank ballots in a national election is a cri de cœur to the disenfranchised masses everywhere to realise their dormant power. The novel is a companion piece to Saramago’s earlier, more celebrated novel Blindness (1995), in which a city is plunged into Hobbesian chaos by a sudden, inexplicable epidemic of blindness, though the connection between the two works (beyond their respective titles) is not made explicit till relatively late in the narrative. Bewildered and increasingly distressed by their apparent rejection by the voters, the politicians of Seeing start to associate this ‘plague of blankness’ with the ‘plague of blindness’ which afflicted the same city four years previously.

But this confused conclusion only confirms their complete misunderstanding of the events which are overtaking them: as the title suggests, and as one of the book’s more astute politicians openly states, the voters’ abandonment of the hollow theatre of electoral politics is rather an outbreak of clear-sightedness. It is crucial to the narrative that Seeing’s ‘blank revolution’ is not planned, but spontaneous. Citizens start wearing badges proudly proclaiming ‘I cast a blank vote’ to express their mutual solidarity, but there is no vanguard party leading the uprising, no conspiracy pulling strings from the shadows. Like Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, a majority of the city’s voters simply awake on election day to the thought that they would prefer not to and are liberated by this insight. It is what Saramago would late describe in his notebook as ‘an insurrection of liberated consciousnesses’.

While the breakdown of the social order in Blindness was in many ways a vision of hell, the withdrawal of state apparatuses following the citizenry’s repeated and increased refusal to participate in re-run elections in Seeing gives rise to a ‘fraternal paradise’. It is tempting to interpret this as a vision of the withering of the state, the political desideratum of Saramago, a lifelong communist, and, furthermore, as an endorsement of Gandhian Satyagraha, or even of the kind of ‘interstitial politics’ that held sway in certain sections of the left in the early years of this century. Theorised by the Marxist sociologist Erik Olin Wright as one of his three forms of social transformation, and later popularised by, among others, Alain Badiou and Simon Critchley, the wager of interstitial politics is that, given the insurmountable hegemony of capitalism, the only place for radical action is not in the direct confrontation with and seizure of state power, but in the gaps or interstices of civil society. Even in 2006, when Olin Wright was writing, the idea was clearly not an original one. It has obvious antecedents in monastic traditions, Charles Fourier’s utopian phalanstères, the American Transcendentalist commune movement of the 19th century and its 1960s and ’70s sequels, and even in certain ancient Eastern belief systems. Its neatest expression in 21st century politics is arguably the title of John Holloway’s enormously (and balefully) influential 2002 book How to Change the World Without Taking Power.

Fortunately, the Left’s attitude towards state power has developed and matured considerably since the turn of the century, but faced with reverses like the defeats of the Corbyn and Sanders projects, the temptations of communes, ghettoes, echo chambers and ‘safe spaces’ of all kinds reassert themselves. This is the lure of what Rodrigo Nunes characterises as ‘intensive revolutions’ (extremely radical, but also highly localised and short-lived) as opposed to epochal, world-changing ‘extensive revolutions’. The city in Seeing can be read in these terms: as a ‘temporary autonomous zone’ beyond the reach of state power. Crucially, however, Saramago knows that the passive, Bartlebyan resistance enacted by the citizens of Seeing will never be sufficient to achieve the extensive revolution he dedicated his political life to; that those currently in power will countenance any crime in the discipline of the unruly rabble, down to mass murder —and indeed this is the fate that befalls Seeing’s ‘blank revolution’. Despite the near intolerable bleakness and cruelty of Blindness, Seeing is ultimately the far more pessimistic work.

Which is to say, simply, that if the ritual of casting a vote every few years is unlikely ever to be sufficient to the collective challenges that face us, then neither, obviously, is abstentionism, however radically intentioned. Only if we take a clear-eyed view of the meaning of elections can we treat our votes not as sacred expressions of our will, but as tactical moves in a struggle that encompasses every aspect of our lives, and that extends to every day, not just election day. As Diane di Prima wrote in her ‘Revolutionary Letter # 8’ (1971), ‘NO ONE WAY WORKS, it will take all of us / shoving at the thing from all sides / to bring it down’.

Let us stand not in silent condemnation. Let us howl.